The notion of Michigan as a climate haven, ripe to receive refugees from hotter, drier states, has gained traction in recent years, with some saying climate change could reverse the state’s dwindling population growth.

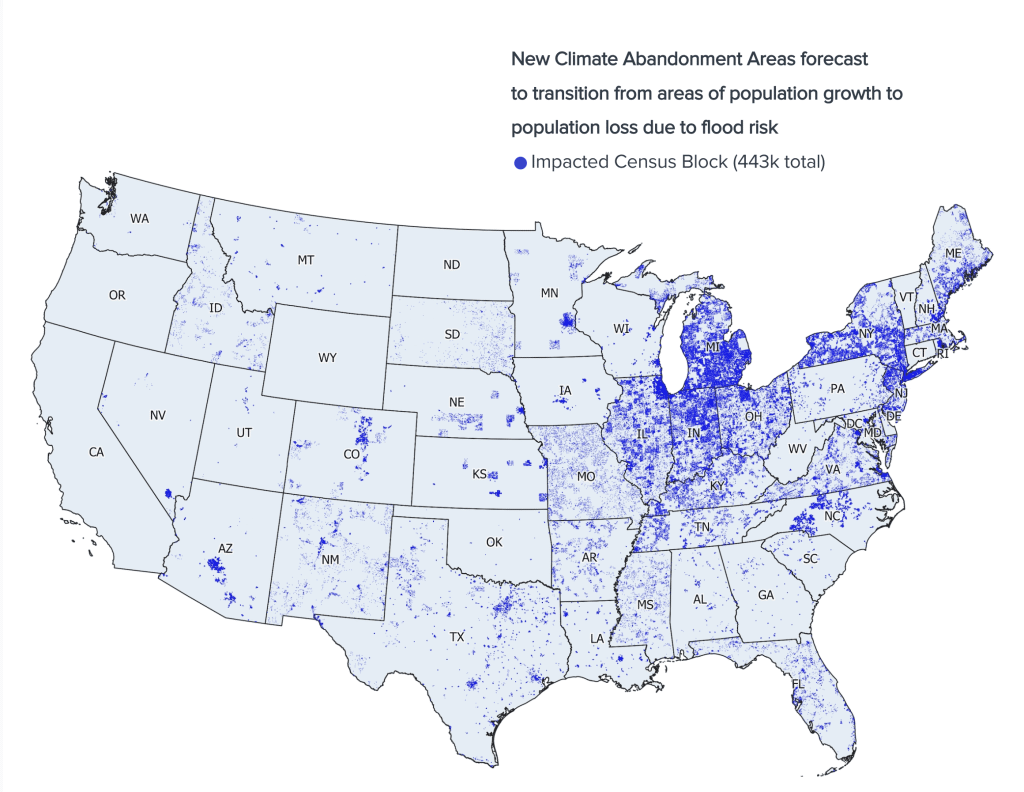

But a new report complicates this idea, predicting that the long-established trend of Midwesterners relocating to the Sun Belt will continue and that flooding in Michigan could create thousands of local “climate abandonment areas” where flood risk leads to population loss while other nearby areas benefit.

The nonprofit research group First Street Foundation’s report found that the Midwest and Michigan can expect to see continued population loss and an increase in climate abandonment over the next 30 years. It also found that while some will likely continue to leave the state, consistent with long-term trends, many will relocate to a less flood-prone area within the same city or region.

According to Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications research for First Street Foundation, this outcome reflects a “house-by-house” response to climate risk rather than a “state-by-state” one. In Michigan, this could look like people abandoning census blocks hit by disasters like basement flooding and moving to neighborhoods with lower flood risk – or better flood control infrastructure – within the same county or region.

First Street predicts that around 5% of Wayne County’s roughly 36,000 census clocks will be impacted by climate abandonment by midcentury.

Yet, the study also projects Oakland and Macomb counties will be among the top 10 U.S. counties for attracting those fleeing flood risk. Some of this growth could come from local moves.

According to the First Street report, 2.9 million, or 26% of the country’s roughly 11 million census blocks have flood risk levels that negatively affect population growth. Most of these places aren’t considered true “abandonment areas” – where the population declines – but rather “risky growth areas” where the population continues to increase despite the negative impacts of flooding.

The study highlights the persistence of long-term moving patterns. Porter called attention to what he said was a misleading narrative that emerged with the COVID-19 pandemic, which held that remote work allowed more long-distance moves.

“Long-distance moves stayed relatively consistent over the last couple of decades, and they actually didn’t tick up that much during the pandemic,” Porter said. Since 2000, around 85% of moves have been local.

Despite growing risk from climate threats like rising sea levels, heat, drought, and tropical storms, projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) show that the population will continue to grow in many parts of the South over the next three decades while most areas of Michigan lose population.

“What we’re seeing in the Midwest is that there’s not a lot in the way of amenities that are drawing people in the same way they are in the South,” Porter said. Sun Belt cities continue to attract new residents because of jobs, relatively inexpensive housing and warm weather despite growing climate risks.

An overall slowdown in U.S. population growth influences the projected decline in the Midwest and Northeast, with the U.S. Census Bureau predicting the population to decrease after 2080.

But while people may continue to move locally or head to the Sun Belt, it doesn’t mean homebuyers aren’t thinking about climate change. A report released by the real estate website Zillow found more than 80% of homebuyers were looking at “at least one climate risk” when shopping for a home.

Porter said this generally means buyers are using local knowledge to find less flood-prone homes close to where they’re already living.

“They want to live in the same place, but they’re moving to higher ground within the same communities,” he said. “You end up with the potential for many climate abandonment areas within the same county, and those people just redistribute themselves into other safer areas.”

However, this study’s focus on flooding and its 30-year timeline may obscure the possibility that other climate disasters could eventually precipitate a northward migration. Porter said that more research is needed and that disasters like heat, hurricanes and drought will likely begin to factor into where people choose to live. But that may take more time.

“If we project out to 2100, you’re going to start to see drought in the West, you’re going to start to see hurricanes in the South, heat in the Midwest that are driving people out of those areas and potentially start to see a larger reversal of that macro trend of Rust Belt to the Sun Belt,” he said.