Overview:

- Grosse Ile’s Hennepin Point is contaminated with toxic distiller blow-off and mercury waste, posing environmental and potential human health risks.

- Regulatory efforts have been slow, with initial pressures in the late 1990s leading to a delayed environmental investigation and ongoing concerns about air quality and groundwater safety.

- To date, the state has not accepted a remedial action plan for the site.

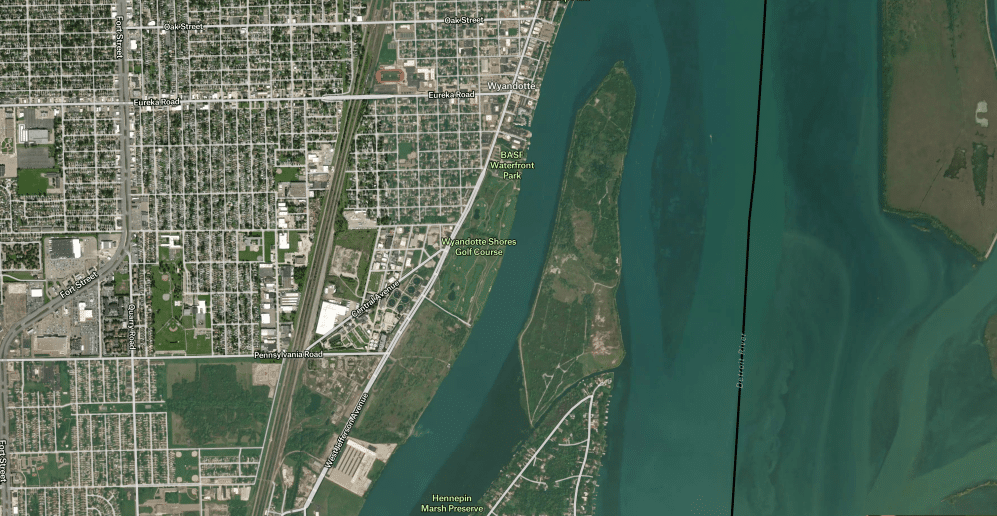

Map of Hennepin Point via Felt.

The terrain covering Grosse Ile’s Hennepin Point, at first blush, appears like any other of the myriad areas around Michigan’s Great Lakes shorelines. Brush and trees grow among patchworks of sand, and the crystal blue Detroit River flows past on either side of the point.

But the sand here is not like most throughout Michigan. It is composed entirely of distiller blow-off, a toxic substance once produced by Wyandotte chemical manufacturer BASF and its predecessors.

The companies dumped DBO on the 225-acre site for decades throughout the 20th century. BASF also stored mercury waste in lagoons and injected it into salt caverns at Hennepin Point around 50 years ago, state and federal regulatory documents show, and regulators are now trying to determine if the complex geological area beneath the island is leaking it or other contaminants. Documents also show that waste drums with unknown materials have been found at the site.

Regulators first began pressuring BASF to assess Hennepin in the late 1990s, and an initial report indicated a “degraded” vegetation and species composition, meaning less wildlife was present than should be expected. The state was dissatisfied with the methods used for an ecological assessment and requested additional investigation. In 2006, the state rejected BASF’s remediation plan. A new one was never approved and no follow-up investigation was started until nearly 20 years later.

Map of Grosse Ile via Felt

The DBO may present a health threat to humans living in the area who could face exposure to the substance when the wind kicks it up, two independent experts and a former Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy geologist told Planet Detroit.

No assessment of air exposure to DBO for those living in surrounding homes has been conducted to date. Long-time officials and residents on Grosse Ile who spoke with Planet Detroit say they were unaware of the DBO and mercury and want BASF or regulators to test the air.

The sluggish progress toward cleanup has generated frustration among local environmental groups and residents like Kyle de Beausset, a Grosse Ile Township board trustee who is also part of the Sierra Club’s Michigan chapter.

“I know BASF considers itself – and is considered by many – to be a good corporate partner to downriver communities, but … I have real concerns with how long it’s taken [them] to clean up legacy sites it’s responsible for along our riverfront, and Hennepin Point is no exception,” he told Planet Detroit.

EGLE spokesperson Hugh McDiarmid attributed the delay to the agency’s limited resources to address the more than 26,000 contaminated sites statewide, which he said forces it to “triage which ones represent the most risk.”

“As is the case with many large and complex sites of contamination, EGLE oversight on Hennepin Point has waxed and waned over recent decades as staffing levels and higher-priority issues fluctuated,” McDiarmid said.

But, he said BASF is “actively working toward remediation.”

However, EGLE and BASF have not committed to air testing, though McDiarmid said it may be done at some point in the new investigation.

BASF already faces increased regulatory scrutiny and pressure over staggering levels of toxic waste leaking from its Wyandotte plant property into the Detroit River. The plant sits just across the Trenton Channel from Hennepin Point.

McDiarmid noted that EGLE has not received alerts from other government agencies or its hotline that allow the public to report issues.

“We have no reason to believe there is any issue there that requires immediate action,” he said.

BASF did not respond to requests for comment.

Brine mining’s legacy

Hennepin Point was originally a now-rare Great Lakes coastal wetland before BASF’s predecessor converted it into a waste field beginning sometime in the 1930s. Though it appears as any other piece of land, the ground is almost entirely made up of DBO, said Steve Hoin, a retired EGLE geologist who worked on Hennepin for around 20 years until he retired two years ago.

The substance is a waste byproduct generated during brine mining of the Salina geological formation located 1,300 feet below Hennepin Point’s surface, which BASF’s predecessor started during the late 1920s. Mining ceased in 1951.

The process involved drilling wells into the ground, pumping in water, and pumping out brine. Waste byproducts include the DBO and ammonia, which elevate pH, producing extremely alkaline groundwater.

Normal groundwater pH is usually 7.3 to 8.1; anything above nine is generally considered toxic, and Michigan’s enforceable limit for high pH in water is 9.5. Groundwater testing on Hennepin revealed pH levels in the 11 to 12 range. Testing for ammonia in 2004 indicated the substance was ubiquitous, exceeding the state’s enforceable limits in 74 samples.

“You can say with confidence that ammonia exists in the groundwater throughout the point,” Hoin said.

Touching highly alkaline water at or above 9.5 pH would likely cause burns or tissue damage in humans, Allen Burton, a University of Michigan ecosystem science professor who studies water contamination, told Planet Detroit.

Experts say that wildlife cannot live in such alkaline water, but pH levels quickly stabilize when the groundwater mixes with the Detroit River, so it is not a threat to the Great Lakes.

However, Burton’s primary concern at Hennepin Point is potential air exposure when the wind kicks up DBO, potentially damaging human lungs or other organs.

Dozens of homes on Grosse Ile sit just a few feet from the BASF property, and those residents could be exposed to the substance when the wind is blowing in their direction.

“It’s just a question of how much of an exposure there is,” Burton said.

Burton said a brief air exposure for someone fishing or recreating on the water would not be a major problem, but said air sampling should be conducted to protect those living nearby. Former EGLE geologist Hoin agreed, as did a chemical exposure expert from Sierra Club Michigan, who reviewed state documents related to the sites. State regulators also raised concerns about air exposure for workers on the site in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

McDiarmid said that air sampling might be part of the new environmental investigation BASF is expected to submit this year, or in the next project’s next phase.

“The work plan we expect soon is to focus primarily on groundwater/surface water interchange as it is our primary concern, but may also include other potential pathways,” he added.

Several current and former residents who spoke with Planet Detroit said they had never heard of the DBO on Hennepin Point.

Kevin Flavin, who lives near the site, said that BASF is a big enough company to afford to do air testing, and wanted state regulators to get on top of the issue.

“If there could be a problem … then they should check it out,” he said.

Vast resources, slow progress

Retired EGLE geologist Hoin notes that BASF’s slow progress in remediating Hennepin exemplifies how large corporations can use their vast resources to resist regulatory pressure.

Hoin recalled negotiations with the company throughout his career that would involve him and one other EGLE staffer on one side, and a large team of BASF attorneys and company officials on the other. The dispute over BASF’s ecological assessment Hoin characterized as “flawed,” is one such instance.

“It became a fight that we didn’t have the manpower for at the time, so that’s still an ongoing issue,” Hoin said.

Hennepin Point’s 225 acres are almost entirely made of DBO, so the cost of cleanup would be “huge,” Hoin noted.

While full remediation of the DBO would require largely removing the substance from the island and restoring the area as a wetland, Hoin said the company could cap the entire site with clean soil and create pH buffers around shoreline edges.

What is less clear is whether the mercury waste BASF sent to Hennepin Point in the 1970s is still contained in the salt caverns. Federal documents show waste shipped to Hennepin Point from 1970 to 1971 contained mercury levels between two and 10 parts per billion.

The waste was temporarily stored in surface lagoons that federal documents reported had leaked until it was stored in deep injection wells. Deep injection welling is a waste disposal process in which toxic waste is sent into wells deep in the earth’s crust, such as Grosse Ile’s Salina formation. Wells have leaked and contaminated groundwater in other locations around the country.

Records show the company sent about 10 pounds to the caverns in just one month, and similar levels in some other months.

EGLE is in the process of identifying routes in which mercury waste could escape. McDiarmid said the agency has found several vents to the river and plans to test them for contaminants this spring.

Because BASF mined so aggressively in the area, it created voids in the Salina formation, Hoin said. The bedrock above it collapsed into the voids, which created sinkholes at the surface of Hennepin Point, and a potential pathway for contaminated groundwater to reach the surface.

Hoin is hopeful the mercury waste stored below is not escaping.

“That would be trouble,” he said.