This story is published in partnership with BridgeDetroit.

- A lawsuit alleges Michigan regulators manipulated air quality data to approve a pollution permit for Edward C. Levy Co.’s plant in Southwest Detroit..

- The suit claims the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) ignored nearby monitors showing high particulate matter levels, using cleaner data from six miles away.

- Donations totaling $65,000 from Levy employees to Gov. Whitmer’s campaign preceded the permit approval.

Michigan regulators manipulated air quality data to push through a pollution permit for a politically connected Southwest Detroit concrete producer, a new lawsuit filed in state court alleges.

The suit charges that the state assessed existing particulate matter levels in the low-income area in which Edward C. Levy Co. plans to build a plant in a way that made the levels appear lower than they are. Had a proper analysis been done, regulators would have found the facilities’ emissions would have caused a violation of federal air quality limits, the suit charges.

The decision to approve the permit by the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) came after Levy employees or trade groups to which they donate gave about $65,000 to Gov. Gretchen Whitmer in the year leading up to the application process.

EGLE’s claim that the Levy plant won’t push particulate matter levels above the legal limit is “disingenuous,” said Andrew Bashi, an attorney with Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, which filed the suit on behalf of several neighborhood groups.

“EGLE has violated air quality laws and regulations that exist to protect community members from dangerous levels of PM2.5 pollution, engaged in arbitrary and capricious decision-making and abused its discretion to the detriment of the very people they have been entrusted to protect,” the suit states. It asks the court to revoke the permit.

Planet Detroit and BridgeDetroit detailed the issues around the permit in an October investigation.

In a statement, EGLE spokesperson Hugh McDiarmid said the agency “is confident the Levy permit meets applicable air quality regulations and is protective of local air quality.”

State records show several Levy subsidiaries have received nearly $500 million in state road contracts from the Whitmer administration.

When asked about the $65,000 in donations, a Whitmer spokesperson responded by questioning whether EGLE had detailed the permitting process ahead of the previous report from BridgeDetroit and Planet Detroit He had no further comment.

Dearborn-based Levy said in an email that its new facility will “lead to reduced CO2 emissions, reduced fugitive dust emissions, and reduced truck travel, all of which is an environmental win.”

State records showed particulate matter levels in the area near Zug Island were already on the cusp of violating federal health limits when Levy submitted the application in 2023.

The additional emissions from Levy’s new plant would have caused particulate matter levels in the region to violate the federal threshold of 12 µg/m3, the lawsuit claims.

It charges that EGLE and Levy got around that problem by ignoring air quality data from monitors near the site. Instead, EGLE and Levy used data from monitors from six miles away in Allen Park, where the air is cleaner.

Moreover, instead of using any of the five monitors closer than Allen Park that could give definitive particulate matter levels, one of which is less than a mile from the proposed plant, the state developed a model to estimate background particulate matter levels.

The model’s estimate is far too low because it did not include some sources of particulate matter emissions that the monitors would have caught, the lawsuit alleges.

EGLE documents obtained during discovery confirm that there would have been an exceedance of the federal particulate matter limit, Bashi said.

“Those standards are meant to protect people breathing in ambient air – anything outside of a facility,” he added

McDiarmid said EGLE sees it differently.

“EGLE’s detailed and thorough review went beyond the minimal federal requirements for a facility of this type and the level of pollutants released,” he wrote in an email. “We look forward to an evaluation of our methodology and decision-making criteria to ensure our work is consistent with the law and with our commitments to the community near the Levy facility.”

Residents living near the site and environmental groups previously lambasted the permit approval, charging that it was evidence that the Whitmer administration put the needs of industry before low-income communities overburdened by pollution.

“They are always talking about environmental justice, but then when the time comes to do something, to make decisions that could help people, they find every way to bend over backwards to make the permit happen,” Bashi said.

However, the plant would play a major role in the Whitmer administration’s efforts to rebuild tens of thousands of miles of crumbling roads. The plant, planned for a five-acre former industrial site on Jefferson Avenue along the Detroit River, would take waste from nearby steel producers and process it for reuse in concrete.

It would be the first in the state to use a process that creates higher-quality road material.

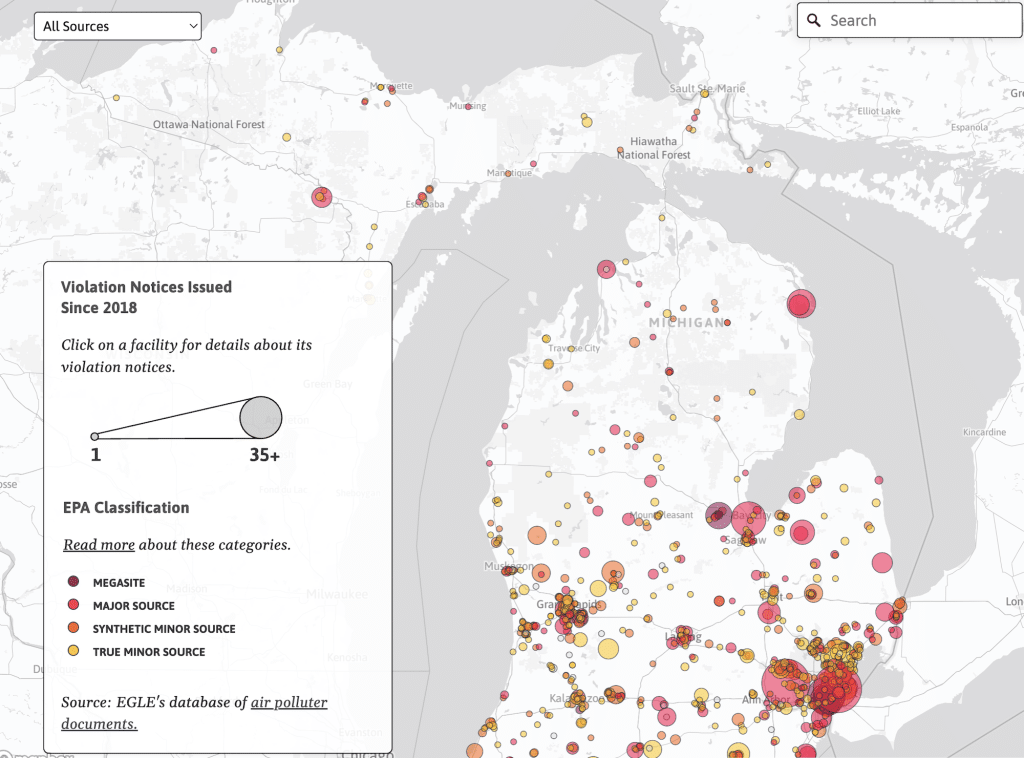

A current nearby Levy plant Is among the state’s most cited for air quality violations, amassing 19 violations over six years. Overall, Levy companies have been cited at least 52 times over the past 11 years, according to GLELC’s review of air quality violation data.

The suit questions why the state did not consider those violations when deciding on the new permit. EGLE said during the permitting application process that it “does not have the legal authority” to reject an application if the applicant complies with all “regulatory requirements.”

But Bashi noted the statute requires regulators to not only consider modeling but also judge whether a permit applicant can operate a facility without violating air quality limits. Ignoring Levy’s history of violations is “absolutely ridiculous and against the law,” Bashi added.

“To us, the statute makes clear EGLE has the authority to look at the whole application, including Levy’s history,” he said. “What’s the best indicator of if they can comply with the law? It’s what they’ve done in the past.”

Editor’s note: Great Lakes Environmental Law Center is a Planet Detroit Impact Partner. Impact Partners support Planet Detroit’s journalism but do not influence or direct our editorial decisions which are made independently.