Overview:

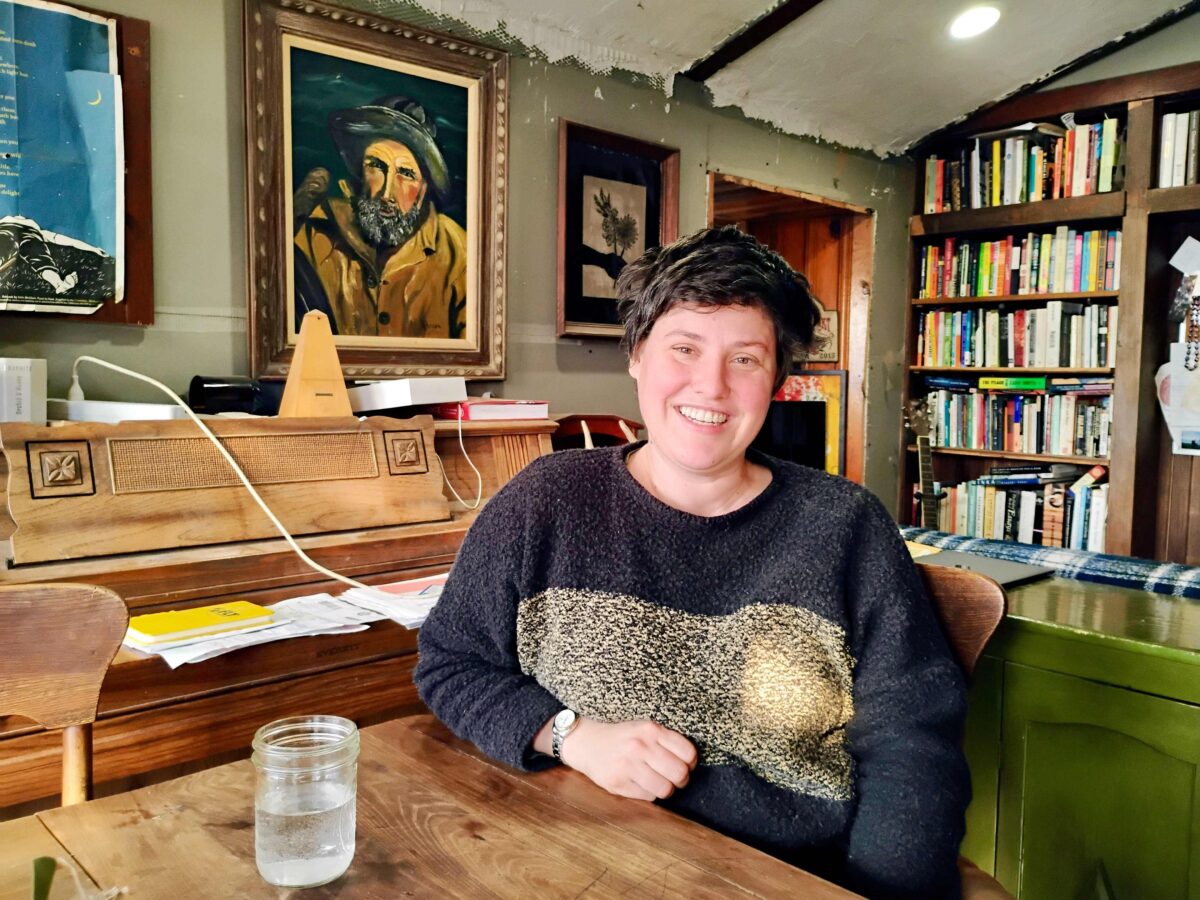

-Attorney Andrew Bashi says his role at the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center is the best job he's had.

-His career path included a detour to veterinary school.

-Bashi "sees the whole person and the whole community," says the center's executive director.

This story is published as part of Planet Detroit’s 2025 Spring Neighborhood Reporting Lab, supported by The Kresge Foundation, to train community-based writers in profile writing. This year’s participants will focus on highlighting grassroots leaders driving positive change in metro Detroit.

“In most places, people can’t flee,” said Andrew Bashi. “They don’t have the option.”

For the last five years, Bashi has worked in Detroit as an environmental justice and community-based lawyer. His clients, he said, have little to lose.

“Their properties aren’t worth much anymore because of industrialization and discrimination. Their only option is to fight.”

Bashi’s work isn’t rooted in policy briefs or politics, but in lived experiences.

“You go into people’s homes, you see the destitute poverty they live in, their hospital records with all these health issues that their kids are facing, issues that you know are probably environmental,” he said.

“You feel a sense of responsibility to at least try to make things a little bit better.”

One lawyer’s path to the courtroom

In law school, Bashi said he learned to combine activism with the practice of law. His legal career has been anything but traditional. He moved from working in criminal defense to conservation medicine, and then to environmental law.

“I tried to find my voice within the legal field,” he said, adding that he wanted to merge his activism with his legal work.

The search led him to work with The People’s Law Office in Chicago, a law firm known for handling cases of police brutality and political activism, and with the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, which he describes as his “dream job.”

By 2012, Bashi said he found there were very few legal nonprofit jobs available.

Instead of giving up, Bashi started his own criminal defense practice in Chicago. Besides courtroom work, he organized “Know your Rights” outreach meetings in places like barbershops in Black neighborhoods, where neighbors tended to congregate, he said.

“It took planning and some work,” Bashi said, adding that he first had to establish trust. “I had to develop relationships with folks who were trusted in the community.”

His empathy, though, made it difficult to separate his work from his life, he said.

“I loved my clients too much, I think,” he said. “When I’d go home, I wouldn’t be able to sleep because I’d be worried about somebody. I was miserable doing the work.”

That led to a bit of detour.

“I really wanted to do something with the environment, and I love animals,” he added. “So I decided to try to go to veterinary school.”

The school he chose didn’t seem to be the right fit, either. “Cornell and I didn’t get along,” Bashi said. And a mentor questioned him. “He told me one day, ‘Man, what are you doing here? You’re miserable. Why would you put yourself through this?’”

The question prompted Bashi to change his focus in veterinary school. He started teaching alongside his mentor in community-based conservation classes. “I loved it,” he said. “It was really, really fun.”

Then he learned of a community lawyer position focusing on environmental justice in Detroit with the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center. It would consist of working with impacted communities on environmental and development issues.

“A bunch of people sent me the same job posting and said, ‘This has your name written all over it,’ and they were right,” he said.

MORE FROM THE NEIGHBORHOOD REPORTING LAB

Detroiter’s activism around I-375 project starts with appreciation for Black Bottom history

Carl Bentley and the ReThink I-375 Coalition question the environmental impact, community involvement, and economic outcomes of Detroit’s $300 million I-375 revamp, and advocate for genuine community partnership in the project.

Brittney Rooney grows food on Beaverland Farms — and community in Brightmoor

Beaverland Farms, a 4-acre urban farm in Detroit, is empowering female growers through full-time employment and sustainable cultivation practices, expanding its reach to local customers and fostering community growth.

Is lifelong learning the key to success? This Detroit teacher says yes

Deborah Jenkins, a Detroit educator, champions collaboration between parents and teachers to secure quality education for children, while pursuing her own lifelong learning.

How Bashi litigates environmental issues

Bashi describes his role at the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center as the best job he’s had. “It’s the way I wanted to do the work … community learning, working directly with impacted communities, and working on the issues I care about,” he said.

Nick Leonard, the center’s executive director, said Bashi brings something out of the ordinary to his staff.

“He’s sort of the person that’s always pushing us to think a little bit bigger, be a little bit more creative, and just fight a little bit harder,” Leonard said. “He never sees anything as outside his role as an advocate.”

One example, Leonard said is how Bashi worked on a civil rights complaint against the Stellantis automobile plant in Detroit. Not only did he file legal grievances, but he also assisted residents with organizing, building their own nonprofit, and lobbying for community needs at large.

“He helped with everything-from making sure residents were heard by the EPA to dealing with a vacant park that has become a nuisance,” Leonard said. “He just doesn’t stop at the legal issue — he sees the whole person and the whole community.”

Bashi resists generalizations about lawyers, especially environmental attorneys. “People think we’re just anti-development,” he said. “That’s not true. There’s a false dichotomy between development and public health.”

For young people interested in working with the law as a means to justice, Bashi offers encouragement, but also a reality check. “Be prepared for a lot of disappointment. The law is not always the be-all, end-all.”

In fact, Bashi suggests not waiting for law school to get involved.

“You don’t have to be a lawyer to submit public comments or help with a freedom of information request. Those things give you real-life experience and connect you to people already doing the work.”