Overview:

-Urban development and industrialization led to Detroit's wetlands being filled in and creeks, no longer needed for crop irrigation, being buried and turned into sewers.

-Modern maps bear some traces of these ghost creeks. Baby Creek, which runs into the Rouge River through Woodmere Cemetery, was buried in the mid-20th century but remains visible on Google Maps, marked with a light blue line.

-"When you remove a river from the landscape, the topography stays," says University of Michigan-Dearborn geology professor Jacob Napieralski.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Detroit River Story Lab, a University of Michigan initiative that supports local efforts to center the river as a site of connection and belonging. The Lab’s local journalism portfolio includes the Detroit River Stories podcast series, the 100 Years Ago Today blog, and the Detroit River Beat, a collection of student-authored stories about the river’s role in sustaining human and more-than-human communities throughout the region.

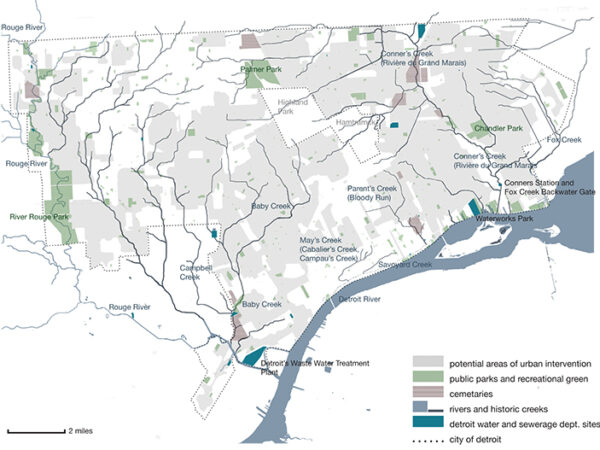

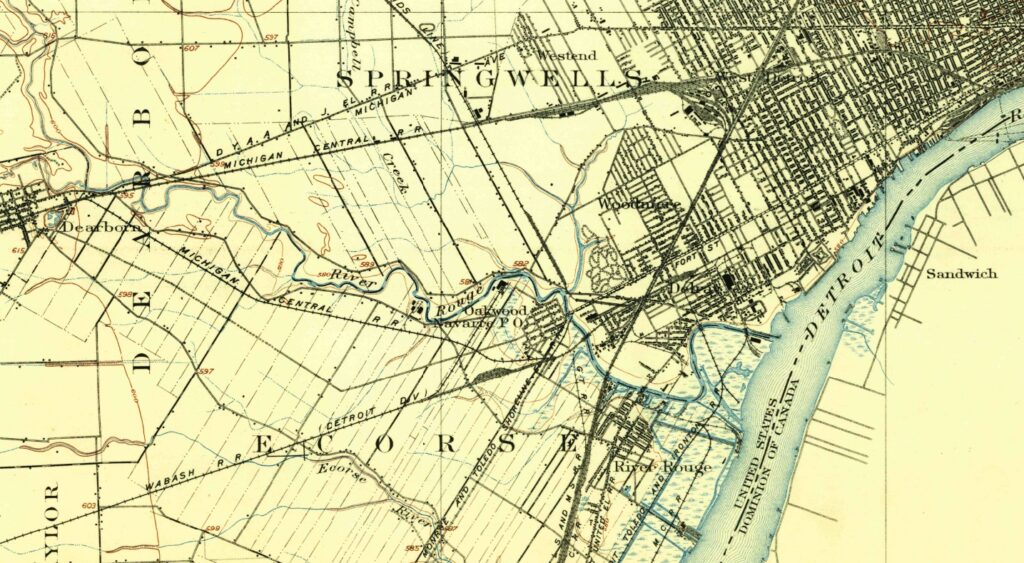

Since moving to Detroit in 2020, Joanne Coutts has explored subterranean Detroit on her bike, using century-old U.S. Geological Survey maps to trace the paths of creeks that now run deep underground.

Coutts embarked on this project, she says, to “navigate the city from the perspective of water rather than of concrete.”

While cars and freeways dominate Detroit’s transportation system today, this has not always been the case. Like many large cities, Detroit was built alongside waterways that were used as vital means of transportation by indigenous peoples for centuries before its founding.

Urban development and industrialization led to Detroit’s wetlands being filled in and creeks, no longer needed for crop irrigation, being buried and turned into sewers. Today, over 80% of the waterways visible on city maps from 1905 have disappeared from view.

Traces of historic Detroit waterways like Conner Creek remain

Modern maps bear some traces of these ghost creeks. Baby Creek, which runs into the Rouge River through Woodmere Cemetery, was buried in the mid-20th century but remains visible on Google Maps, marked with a light blue line. Conner Creek, marked by only a pin on Google Maps, once followed a path now traced by Conner Avenue.

Old newspaper archives offer further clues about these vanished waterways. Articles dating from before a given creek’s disappearance are often speculative, such as one from the 1870s proposing that the city “dredge out the swampy land which lies a mile beyond the boulevard so as to form a canal from the head of Connor’s creek to the head of Baby creek, which flows into the Rouge.”

According to this plan, instead of acting as a sewer or drainage system, the creeks would “form a continuous ship canal around the city” to provide easy access from the river to future factory sites.

Articles published after the burial of waterways tend toward nostalgia. Several articles from the 1870s mourn the loss of the River Savoyard, a creek that ran through the heart of the city, which used to be a place for fishing in the summer and ice skating in the winter. By 1835, it was polluted by sewage.

A piece wistfully entitled “They Used to Fish Here,” published in 1929 by the Detroit Free Press, reminds the reader that “where towering buildings today stand beside crowded city streets, the Detroit fishermen of a century ago sat on grassy banks and cast lines into quiet, sparkling streams.”

MORE GHOST STREAM COVERAGE

VOICES: On the lost opportunities for building a sustainable hydrologic system in Detroit

Mary Wright and her neighbors in Boston Edison face flooding from inadequate sewer drains, as architects and city officials work to address the city’s flooding issues.

OPINION: How ghost streams and redlining’s legacy lead to unfairness in flood risk, in Detroit and elsewhere

Extreme weather events put pressure on cities like Detroit that have aging and undersized stormwater infrastructure, with low-income urban neighborhoods tending to suffer the most.

How Detroit’s ‘ghost’ streams can be a threat today

When heavy rain pours, buried ghost streams flow, flooding Detroit’s most vulnerable neighborhoods and causing significant damage.

Detroit’s ghost streams: hidden flooding hazard

Some articles seem to foreshadow the water issues that too many Detroit residents face today. In 1949, the Detroit Free Press published an eerily prescient piece that opens by advising readers: “Your house may be on the banks of Campbell, or Fox or Conner Creeks—streams that still flow gently through the heart of residential Detroit.”

The story said that some neighbors blamed the buried creeks for flooded basements on the grounds that rain waters likely “follow their old course to the streambed.” City engineer George R. Thompson is quoted as scoffing at such a notion, saying “the rivers in tubes are bigger and much more efficient than they were when they ran between banks.”

Today, we know that concerned residents were, in fact, correct. Residential flood risk is correlated with proximity to a buried stream or wetland area, and cities with higher numbers of buried streams face increased flooding due to climate change, according to Jacob Napieralski, a geology professor at the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Detroit’s “ghost streams” have become a kind of hidden hazard, raising the risk for flooding in neighborhoods built along their former banks. Napieralski’s team studied the reasons for flood risk in areas in northwestern Wayne County and found that buried channels were the most common flood risk.

“When you remove a river from the landscape, the topography stays,” he said, adding that when such an area receives excess rainfall, “water is going to naturally collect where it thinks the river or channel is supposed to be.”

Figuring out where exactly an ancient riverbed is located is far from straightforward. While both Napieralski and Coutts regularly refer to the 1905 USGS map, it unfortunately omits the waterways already buried beneath Detroit’s growing downtown.

The lack of a definitive dataset of buried waterways is one significant hurdle to expanding this kind of research nationwide, Napieralski said.

“I’m not aware of any (cities) that have a complete dataset of buried rivers,” he said, “Let alone (one) integrating it into stormwater systems, runoff systems, anything like that.”

Every city, county, and state will have to come up with its own datasets and policies, he said. While this is challenging, it needs to be done, Napieralski said.

“We can’t ignore the data, which says that flood risk is connected to buried rivers.”

Kalamazoo’s creek daylighting success story

Detroit’s Jefferson Chalmers neighborhood has suffered serious flooding in recent years. Data from 1800 shows the neighborhood sits atop a wetland that’s no longer a wetland, Napieralski said.

“So there’s your connection: you drain the wetland and you put houses — flooding follows. You drain a river and you put houses — flooding is going to follow.”

As the climate crisis worsens, water infrastructure — hydrants, sewers, channels, reservoirs, culverts, and treatment plants — is under increased scrutiny and pressure across the country.

Within the last nine months alone, Los Angeles’s reservoirs and fire hydrants have come up dry in the face of a wildfire burning out of control. Massive flooding in North Carolina and Tennessee washed away lives and livelihoods in countless, close-knit communities. In both instances, the water systems, both natural and infrastructural, have been unable to accommodate the onslaught of unprecedented, but now increasingly normal, weather events.

Detroit has faced recurring episodes of severe flooding, episodes that city officials have directly connected to overloaded water infrastructure. With weather patterns intensifying across the country, finding ways to make urban infrastructure more resilient is essential.

One technique for building that resilient infrastructure is creek daylighting, or opening buried creeks back up to the surface. Some creek daylighting projects work to restore the landscape to a natural state. Others involve what the American Rivers Organization calls architectural restoration, in which a stream is open to the air but surrounded by concrete.

In cultural restoration, a stream stays buried, but placards or art installations mark its historical path in order to increase public awareness.

Many of these projects in the U.S. are in smaller cities, like Saint Paul, Minnesota or Berkeley, California. One early daylighting success, often cited in reporting and research on the topic, is mere hours away from Detroit.

In Kalamazoo, 1,550 feet of Arcadia Creek, which runs through the city’s downtown area, opened as part of a bigger urban renewal project. Like many such projects, it carried a high price tag: $7.5 million to daylight this section of the creek.

While proponents of daylighting cite Kalamazoo’s project as an example of the potential benefits of these projects — including the fact that nearby businesses no longer need to carry flood insurance — it is not easy to replicate.

Community-led creek restoration efforts make the invisible visible

Cultural restoration, which prioritizes strengthening public awareness of the presence of buried waterways, serves as an alternative or supplement to daylighting projects.

Projects by artists, activists, urban geographers, and environmentalists have popped up around North America. In Baltimore, artist Bruce Willen created a public art installation and walking tour, “Ghost Rivers,” that aims to make visible the path and history of one buried creek in the city, Sumwalt Run.

A wavy blue line marks the creek’s path, which cuts across intersections, sidewalks, and road verges. Its diagonal angles highlight the contrast between these natural divisions in the land and those artificially imposed.

In cities like Oakland and Toronto, volunteers have hosted walking tours of buried creeks. In San Francisco, a project by designer Emily Schlickman and audio producer Kristina Loring, “Ghost Arroyos,” marked the history of Hayes Creek, an ephemeral creek that ran through the heart of the city.

“Ghost Arroyos” features recordings of soundscapes that are meant to imagine what the creek might have sounded like, alongside oral histories.

In Detroit, Coutts’ ongoing mapping project acts as a part of a larger local and regional movement to raise awareness of the history and present state of water infrastructure.

Other cultural restoration projects are done alongside stream daylighting efforts. In Saint Paul, Minnesota, community organizers have been working for nearly three decades advocating for Phalen Creek.

They turned their attention to daylighting the creek in 2019. Known today as Wakan Tipi Awanyankapi, the community organization behind this daylighting project is Native-led and oriented around the idea of environmental stewardship.

The project is not only about environmental restoration or stormwater management. It also frames daylighting as a way to “reconnect with water and nature” and with “medicinal plants and traditional food,” emphasizing the important cultural role of waterways and the ecosystems they support.

Even in locations where daylighting is not practicable, raising awareness of buried waterways among community members and homeowners can be beneficial. Napieralski sees awareness as one of the key aims of his work as a researcher: “The idea is to provide the best quality data to residents in a language that they understand.”

This knowledge will empower residents looking to purchase property, making clear that certain homes will carry a higher flood risk due to their proximity to buried creeks, and providing information about forms of green infrastructure that can help to mitigate flooding, Napieralski said.

With that knowledge, community members and neighborhood organizations will be equipped to advocate for themselves, pushing “politicians and planners to make better decisions for their community,” he said.

There may be no daylighting project in Detroit’s immediate future, but thanks to work by Napieralski, Coutts, and community groups like the Jefferson Chalmers Water Project, knowledge of the creeks and wetlands buried beneath the city, including the histories behind them and the hidden hazards they pose to today’s residents, is much easier to access and act upon.