Overview:

- U.S. House bill introduced by Rep. Rashida Tlaib seeks to expand FEMA assistance eligibility and coverage, including full basement damage and mold mitigation.

- FEMA policy for basements covers damaged furnaces and water heaters. Personal property, carpeting, and furniture are not covered.

- "There needs to be some equity in terms of what FEMA will pay for," says Kristin Taylor, a WSU political science professor.

As a queen mattress surfed past her house, Barb Matney struggled to keep her composure. In a matter of hours, nearly 6 inches of rain had fallen across Metro Detroit, filling her basement with stormwater and forcing neighbors to discard their waterlogged furniture and belongings onto the curb.

“I stood in my kitchen window and I was so afraid,” recalled Matney, who lives in the Warrendale neighborhood on Detroit’s west side. “You could hear it in my voice, I was almost getting ready to burst out into tears.”

In the aftermath of the August 2014 storm, Matney said, her family lost “$52,000 worth of stuff,” including her furnace, water heater, washer, and dryer.

One of the most upsetting aspects of the storm, she says, was the loss of her college-age son’s clothes, furniture, and belongings. Until the flood, he stored his keepsakes in their basement.

When it comes to basement flooding, households across the United States have limited reimbursement opportunities for belongings and structures damaged by stormwater. That’s because disaster aid and insurance administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, does not cover personal property kept in basements.

For Matney and thousands of other Southeast Michigan residents, that means they’re excluded from receiving additional dollars to completely address the flood damage inside of their homes.

HUD estimates there was $142 million of unmet need following the 2021 flood. The city received $57 million from a Congressional appropriation after the flood, according to a 2022 city report.

An estimated 32,000 to 47,000 households, 82% which were low-to-moderate income, were directly impacted by the 2021 disaster, majority of those located in City Council Districts 4, 6, and 7.

A bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives this summer aims to address the ongoing issue while targeting the lingering health impacts of flooding.

In July, U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib, a Detroit Democrat, introduced H.R. 4774, the Fix Our Flooded Basements Act, to expand federal disaster aid coverage for repair and replacement costs due to basement flooding damage, and provide funds for mold and mildew remediation.

“I really want to ensure the maximum amount of federal disaster assistance for our families for immediate recovery,” Tlaib told Planet Detroit. “The goal is to cover the whole house and make sure basements are covered.”

FEMA’s work must reflect Midwest climate risk, Tlaib says

Tlaib introduced the bill because of the number of residents in her district who have reached out to her in search of help for the hazards in their basement, she said.

Two years out from the August 2023 flood, the last federally declared emergency in Southeast Michigan, Tlaib said she’s still receiving calls about toxic mold.

“It is so bizarre as a member of Congress, finding out that FEMA will come and cover getting a new furnace or water heater, but won’t actually cover the actual mitigation and cleaning up of the sewage and the water in people’s basements,” Tlaib said at an Aug. 19 news conference about the bill.

Federal policy offers limited coverage for basement damage, she added, ignoring the prevalence and importance of basements in regions outside of traditional natural disaster areas.

“FEMA was created, for many reasons, for coastal communities, but now the Midwest is directly impacted by those doing nothing about the climate crisis, and so we have to make sure that all these federal agencies are adapting to that and not leaving communities like ours behind.”

The Fix Our Flooded Basements bill would change language in the Stafford Act, a federal law that oversees FEMA disaster relief, to expand eligibility and coverage under the agency’s insurance policies and assistance funds and for mold remediation and flooding damage to basement appliances, carpet flooring, and personal property.

At the moment, there is no action on Tlaib’s bill. Since introduction, it’s been referred to the House Committees on Financial Services and Transportation and Infrastructure.

If the bill becomes law, homeowners with flooded basement damage would be able to utilize FEMA’s Individuals and Households Program, which provides up to $43,600 for temporary housing, home repairs, and hazard mitigation. The Fix Our Flooded Basements Bill would also expand eligibility for FEMA’s Group Flood Insurance Policy.

‘There needs to be some equity’

An amendment to the Stafford Act, which was last updated in 2018, would reflect the ever-changing climate reality for communities such as Metro Detroit, said Kristin Taylor, a political science professor at Wayne State University, who studies the politics of natural disasters and disaster recovery efforts.

“There needs to be some equity in terms of what FEMA will pay for,” said Taylor. “If everything that FEMA is doing is geared towards reimbursing costs for people who live in hurricane prone areas, then it’s definitely an inequity compared to people who don’t.”

Severe rainstorms compound on the region’s histories of redlining as well as the ongoing stormwater infrastructure problems, she added.

The Fix Our Flooded Basements Bill so far has received endorsements from nearly a dozen local community organizations, as well as sponsorships from 22 U.S. representatives, including U.S. Rep. Shri Thanedar (D-Detroit).

“Flooding is one of the top concerns I hear about from my constituents,” Thanedar said in a statement. “Just 1 inch of water can cause up to $25,000 in damage and leave families with long-term health risks from black mold.”

LeJuan Council, founder and director of Detroit Area Disaster Recovery Group, has witnessed it firsthand. She’s spent the last decade addressing environmental and public health issues such as groundwater flooding, sewer backups, and mold exposure throughout the city.

Many city residents not only store their belongings in their basements, but use them as a living space, Council said. The Stafford Act doesn’t account for this, nor does it directly assist with the mold and mildew problems that residents experience long after the storm.

“When you see that visual of everybody’s belongings curb to curb, with their things piled up 4 feet tall and 10 feet wide, that stuff will never get paid for and that’s hard because (that’s) $30,000, $40,000, $50,000 worth of stuff,” she said.

MORE REPORTING BY ETHAN BAKULI

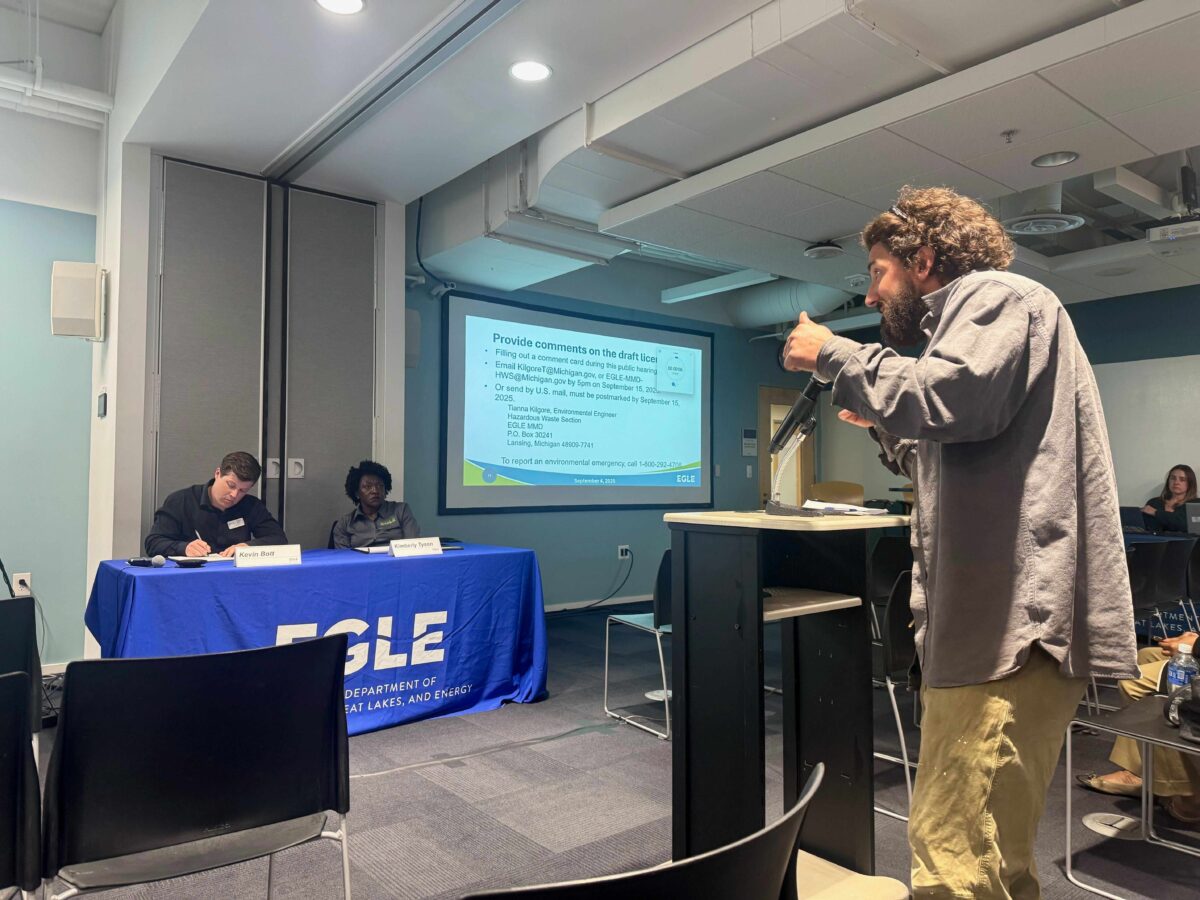

US Ecology hazardous waste facility’s neighbors urge license rejection: ‘Who wants to live in a place that’s massively polluted?’

Michigan’s environmental regulator issued an air quality violation for a US Ecology hazardous waste facility in Detroit on the same day as a public hearing on its license renewal.

Michigan’s environmental regulator holds east side workshop after civil rights complaint on Stellantis permit

Michigan’s environmental regulator agreed to hold an informational meeting with the community around the Stellantis plant in its informal resolution with the EPA of a civil rights complaint.

Detroit River nonprofit targets wetlands loss with island habitat restoration

The Detroit River lost “probably 95%” of its coastal wetlands, “particularly on the Detroit side,” says riverkeeper Bob Burns.

The ripple effects of basement flooding

The fact that FEMA assistance has not fully covered basement repairs and replacements has only compounded the frustration residents feel, said Council, who adds that her advocacy work involves educating “residents on what FEMA can and can’t do” and encouraging people to re-apply to the agency with more information when their original application is denied.

In Matney’s case, her family received $8,000 from FEMA to replace major appliances and repair her basement drywall after the August 2014 floods. While the aid didn’t cover the estimated $52,000 of expenses the family accrued, she said they “were lucky that FEMA helped take care of us.

“Some people got less than others, which I never did understand,” said Matney. “It was just very weird to me. We did OK, but then the neighbor next door only got $500.”

Matney and her husband purchased a sump pump, and handled the majority of their basement repairs by themselves.

“We didn’t have the money to hire anybody, so we ended up doing the cleanup all ourselves,” she said.

“We ended up cutting all the drywall, pulling it all out. It was a lot of bleach, a lot of mildew cleaner. I just did a lot of reading to find out what we needed to do and then after that, it was time for the rebuild.”

A decade removed from the August 2014 floods, local nonprofits say the challenges still linger for residents trying to repair and replace their damaged basements after each storm.

“It’s not as cheap as it used to be to be able to go, ‘Oh, I can just replace this drywall and change out this and fix that,’” said Chris Hicks, interim executive director of community development at Wayne Metro Community Action Agency.

During the June 2021 flood, when the agency teamed up with other area nonprofits to clean up basements and handle mold remediation, Hicks said he saw repair costs ranging from $5,000 to $40,000.

“Those expenses have climbed significantly … it’s hard to mitigate a lot of those risks,” he said.

The limited federal assistance for basement flooding damage has ripple effects, Hicks said. If structural damage is improperly or slowly addressed, a repair can balloon to “a bigger problem, and it becomes health issues.

“Some of the damage is so extensive that it sometimes disqualifies people from being able to get weatherization services, because it comes to a point that some of the things that need to be replaced and repaired have gotten so worse that they’re now capital improvements to a home,” he said.

Like Matney, east side resident Meghan Richards received FEMA assistance after the 2021 flood. While she was able to pay for a new HVAC system, it hasn’t stopped her from worrying about the next storm or what other fixes she needs.

“I was able to get it replaced through a program that provides you with high efficiency HVAC appliances, but the actual damage probably was more … my basement probably still needs repairs,” said Richards, who is an assistant director of climate equity at Eastside Community Network.

If passed, Hicks said he believes the Fix Our Flooded Basements Bill could “support some of the people that are living in those basements, or still aren’t able to go into their basements because of how expensive that damage is.

“I know a lot of people that haven’t been able to either be back in their homes, or are still actively avoiding their basement,” he said.

Warrendale couple takes community-minded approach to flooding

Since the August 2014 storm, Warrendale’s Matney said one of the hardest things she’s dealt with is “recovering from the fear of it happening again.”

In the immediate days after the water receded, she could see how many of her neighbors were struggling from the emotional and physical toll of the flood.

“We drove around after the street flooding went down, and the people that were sitting on their porches, you could tell that they were depleted,” she said.

In the decade since that storm, Matney and her husband have taken on a multipronged project to foster more connection and neighborhood pride. Since 2015, the couple has turned vacant lot space around their home into a community garden, a park, and an in-development multicultural center.

One core aspect of the project: ensuring rain gardens are strategically placed in the park, “so all the water off of the pavilion goes down under the gym equipment and feeds the rain garden,” Matney said.

“During some of the floods that we have had, the water was so high in the street that it actually flooded the rain garden,” she said. “But the rain garden did what it was supposed to do. Within 48 hours, the water was gone out of that area.”

While the rain garden itself isn’t a fix to the region’s stormwater infrastructure problems, it offers peace of mind for Matney and some of her neighbors.

🗳️ Civic next steps: How you can get involved

Why it matters

⚡ A U.S. House bill introduced by Rep. Rashida Tlaib seeks to expand FEMA assistance eligibility and coverage, including full basement damage and mold mitigation. If passed and signed into law, the bill could provide additional financial aid to Southeast Michigan residents in the direct aftermath of floods.

Who’s making civic decisions

🏛️ The Fix Our Flooded Basements Bill was introduced to the U.S. House of Representatives July 25. It needs to be passed by the House, U.S. Senate, and signed by President Donald Trump to become law.

How to take civic action now

- ✏️ Sign up up to volunteer with After the Storm, a long-term disaster recovery group, to help with carpentry, construction, and remediation in the aftermath of a flood.

- 📩 Email Detroit Area Disaster Recovery Group to learn more about their long-term recovery efforts.

- ☎️ Call Detroit Water and Sewage Department’s customer service and emergency line at 313-267-8000 and file a claim if you experience a sewer backup or flooding. You can also find flood safety information on the DWSD website.

- 🔎 Find your local U.S. representative via ZIP code and contact them by phone, email or snail mail to share your thoughts on the bill.

What to watch for next

🗓️ At the moment, there has been no action on the Fix Our Flooded Basements Bill. On the same day it was introduced into the U.S. House, it was referred to the House Committees on Financial Services and Transportation and Infrastructure. You can follow along with any action on the bill via Congress.gov.

⭐ Please let us know what action you took or if you have any additional questions. Please send a quick email to connect@planetdetroit.org.