by Eryn Williams

When you watch a dance performance, it’s easy to be swept away by the beauty, energy and precision on stage.

You find yourself amazed at how the dancers seem to memorize every step, how the music pulls you in, and even wonder who the artist is behind the song. From the outside, it all looks effortless.

But behind the flawless performance, things aren’t as simple as they seem, especially for Black professional dancers. Many deal with discrimination, limited opportunities, and bias in casting, costumes, and leadership positions. Audiences applaud the art, but they rarely see the sacrifices Black dancers make to be on that stage in the first place.

Many dancers feel they have to constantly prove their worth by perfecting every skill, performing at a high level every day, competing for roles and bringing emotions to movement.

Black creators play a major role in shaping dance trends. But when it comes to recognition and opportunities, they are often overlooked. Despite their influence, they don’t receive equal treatment compared to non-Black peers, a reality that holds them back from reaching their full potential.

“When it comes to costuming and traditional roles, there is bias toward dancers of color,” says Grace Martin, a ballet instructor and choreographer in Canton.

One of the most competitive styles of dance is ballet. Historically, it has also been one of the least diverse. In the 20th century, Black children who studied ballet were forced into segregated studios, a result of the Jim Crow era. Black dancers had fewer teachers, smaller studio spaces and fewer opportunities than their white counterparts.

This issue continues today. A 2023 University of Connecticut study found that U.S. universities offering a ballet degree reported that 62% of the ballet degrees were awarded to white dancers, 20.5% were awarded to Latinx dancers, 5.13% were awarded to Asian dancers, and only 2.56% were awarded to Black dancers in 2017.

To combat the discrepancies, Black dance companies began to elevate their offerings, highlighted by companies like The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Dance Theater of Harlem.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater was founded by Alvin Ailey in 1958 in New York to celebrate and show African American culture through modern dance. Arthur Mitchell founded Dance Theatre of Harlem — the first Black principal dancer at the New York City Ballet — after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a way to inspire young Black dancers.

“I specifically trained in a Black dance program and have for the span of my career thus far,” says Lauryn Simmons, an alum of Power Dance Company in West Bloomfield.

“But I think the opportunities that rise toward Black dancers are from companies who want to see us succeed and who want to offer us training,” she adds. “Seeing big name dance companies reach out to local communities and offer dancers intensive training opportunities and auditions doesn’t go unseen, and it’s valuable especially to Black dancers. It provides a sense of knowing where companies’ mindsets are toward equal equity for dancers of color.”

Outside of opportunities, Black dancers still face challenges that their non-Black peers rarely have to think about. An example is costuming; Black dancers have to find the right shade of tights or shoes that match their skin tone, which isn’t always available.

“Not having pointe shoes that match your tights and having to put in the extra work to dye your ribbons or to paint your pointe shoes or to dye your tights?” Martin says. “Things like that are just an extra load on dancers of color that doesn’t exist for dancers who are white.”

The struggle for fairness and inclusion underlines the importance of raising awareness and taking action within studios, companies and the performing arts community.

Coaches, choreographers and dancers are trying to build a more supportive and equitable environment by speaking out about issues. These collaborative efforts are critical to achieving a future where all dancers are appreciated equally for their artistry and aptitude, allowing the dance industry to represent the diversity and depth of its communities genuinely.

This piece is part of the Detroit Journalism Summer Camp, run by The Detroit Writing Room in partnership with Planet Detroit.

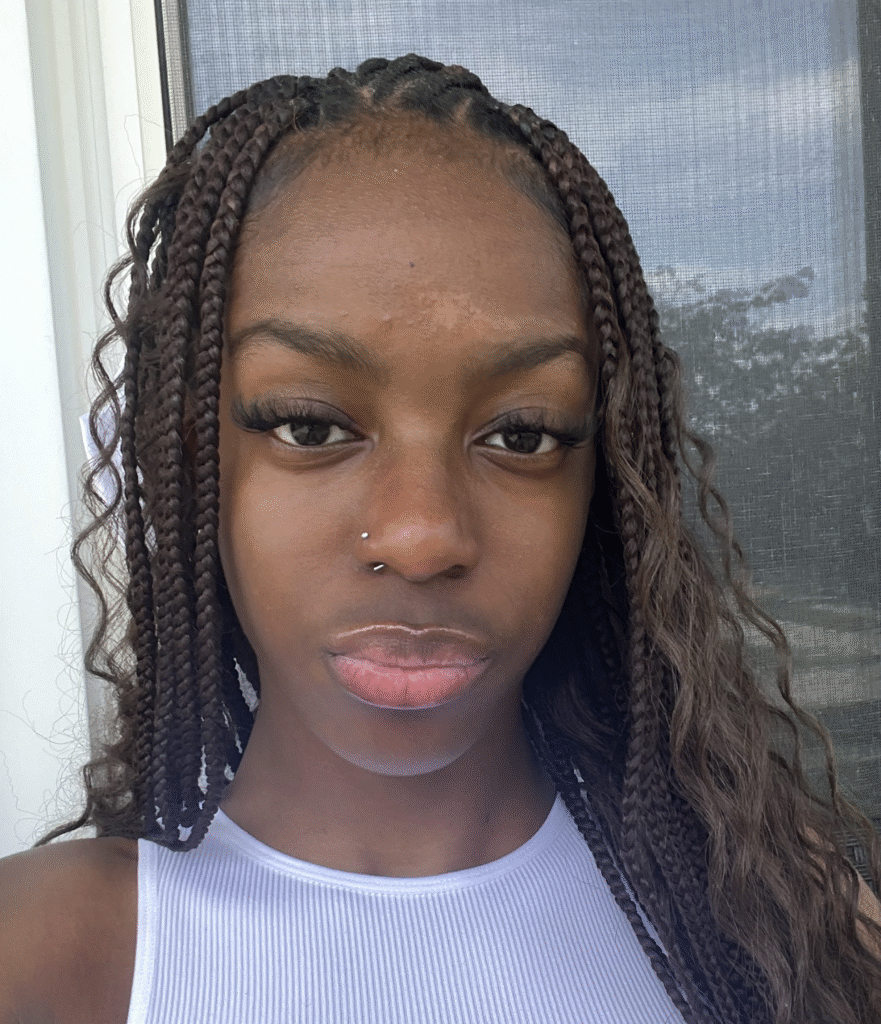

Eryn is a senior at the Detroit School of Arts. She joined The Detroit Writing Room Journalism Camp because she wants to try new things and strengthen her writing skills. Eryn enjoys listening to music, dancing, fashion and photography.