by Kelly House, Bridge Michigan

August 20, 2025

- A new report questions whether Great Lakes states are wooing data centers without fully considering the impacts of their massive water demands

- The report comes as new tax breaks lure the industry to Michigan, with several proposed data centers in the pipeline

- An average facility can easily consume more than 1 million gallons daily

Great Lakes states like Michigan risk overtaxing water supplies by rushing to woo hyperscale data centers without closely analyzing whether local aquifers and water utilities canfulfill the facilities’ massive water demands.

So says a new report from the regional environmental group Alliance for the Great Lakes, which recommends a host of fixes including requiring developers to publicly disclose their expected water use early in the planning process, imposing water conservation and efficiency standards on large water users and mapping and measuring groundwater supplies to help economic development officials make better choices about where thirsty industries can safely set up shop.

“There’s a tension right now between promoting economic development and protecting water resources at the same time,” said Helena Volzer, the alliance’s senior source water policy manager, who authored the report.

As one of the most water-rich regions on the planet, the Great Lakes may seem immune to the pressures that have drained aquifers and strained municipal supplies in the South and West. But the Great Lakes region, too, has experienced localized shortages caused by drought and overpumping of well water.

Now, the artificial intelligence boom, critical minerals gold rush and climate change are all placing new strain on water resources. The report warned that Great Lakes government officials are “simply not prepared.”

“If states, local governments, and economic development agencies do not begin incorporating water availability and demand into their decision-making processes, it may lead the region down a dangerous, unsustainable, and inefficient water use path that impacts drinking water supplies, businesses, and food production,” Volzer wrote.

Data centers, or large server farms used to power artificial intelligence, social media algorithms, online gaming and other data-intensive pursuits, are proliferating across the country, with demand expected to rise by 33% annually through the end of the decade.

In addition to gobbling electricity, they can use massive amounts of water, depending on what technology is used to cool their servers.

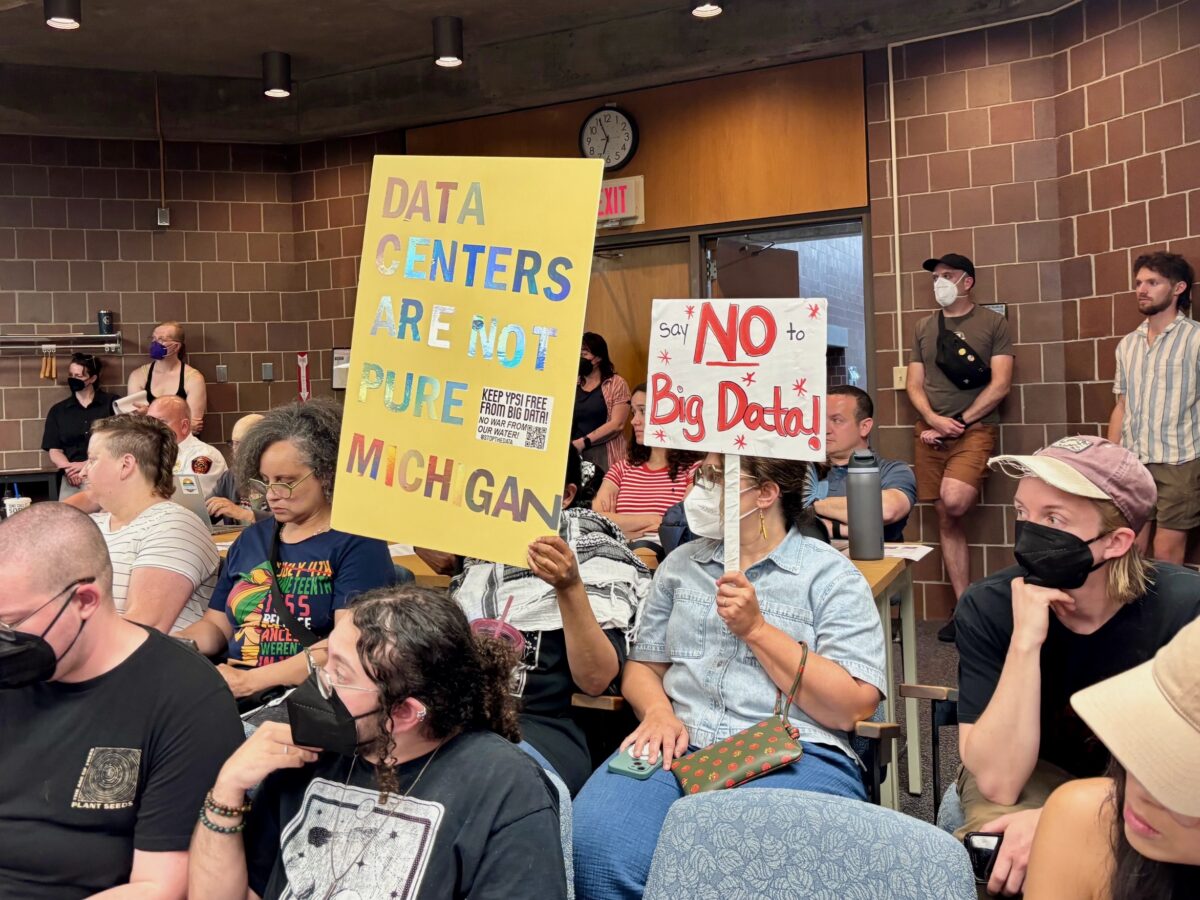

Concerns about that energy and water use came into focus last year as Michigan lawmakers authorized new tax breaks to lure the facilities to Michigan despite protests from environmentalists and ratepayer advocates who argued for more safeguards to keep data centers from overtaxing water supplies and torpedoing Michigan’s clean energy goals.

In order to receive the incentive, data centers must tap into municipal supplies that have available capacity to serve them — a provision Volzer praised.

But she questioned whether Great Lakes states need to incentivize data centers at all, given the water-rich region’s inherent appeal to developers that are running up against water shortages in data center hubs like Georgia and Arizona.

Michigan’s new tax breaks appear to be achieving their intended purpose. The state’s largest utilities, DTE Energy and Consumers Energy, are both courting multiple large data center developments.

During a July 29 earnings call, DTE President and Chief Operating Officer Joi Harris said the utility is in “advanced discussions with multiple hyperscalers” for over 3 gigawatts of new electricity load.

Consumers energy has inked an agreement to supply power for a 1 gigawatt data center at an undisclosed Michigan location and is projecting up to 15 gigawatts of data center load by 2035.

With most of those prospective deals still in their infancy, water use details are unclear. But a proposed Thor Equities data center campus in Washtenaw County’s Augusta Township offers an insight into the potential scale of water demand.

That proposed facility would consume more than 1 million gallons daily — a typical ballpark figure for hyperscale centers cooled through evaporative cooling, which uses water vapor to cool equipment. It’s equivalent to the household water demand of about 12,000 people.

Centers with closed-loop cooling systems, in which coolant is recirculated through pipes, use far less water but often more energy. They’re also less common.

“The Township will need to consider how much water the facility will need and if it can be provided,” stated an analysis of the proposal written by the township’s planning firm.

Officials with the township and its water utility, the Ypsilanti Community Utilities Authority, did not immediately respond to calls from Bridge Michigan about whether supplies are sufficient to meet the proposed facility’s needs.

Data center advocates note that many Michigan water utilities have plenty of excess capacity after major customers like auto factories closed up shop in recent decades. For them, the prospect of a new major water user is exciting, not threatening.

In Michigan, water permits are typically required for users planning to withdraw more than 2 million gallons daily and data centers tapping into water utilities will need to first ensure the utility has adequate capacity.

Given those requirements, “a data center is going to be highly disincentivized from going into a community where they think they might negatively impact the drinking water or their local aquifer system,” said Mike Alaimo, legislative and external affairs director for the Michigan Chamber of Commerce.

But often, Volzer said, nondisclosure agreements signed by companies and public officials keep details about water demand hidden from the public until construction is underway.

While the industry argues NDAs are necessary to protect sensitive information from competitors, “I really question” the value of shielding information about public water and utility usage, Volzer said.

Beyond data centers, the report highlighted expansions of irrigated agriculture and critical minerals mining as emerging Great Lakes water issues.

As climate change heats the earth’s atmosphere, farmers are increasingly tapping groundwater to irrigate crops in areas that used to rely solely on rainfall. And mines, like those being proposed in Michigan and other Great Lakes states amid a rush to develop domestic supplies of nickel, lithium and other minerals used in electric vehicle batteries and other technologies, use lots of water to process ore into metals.

This article first appeared on Bridge Michigan and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

learn more

Ballot drive kicks off to put Washtenaw County data center decision in hands of voters

Augusta Township residents are gathering signatures to challenge a rezoning decision for a planned $1 billion data center. Concerns over rising utility costs, environmental impact, and grid strain drive their efforts.

University of Michigan’s ‘big bad data center’ faces opposition from top Ypsilanti Township official

Supervisor Brenda Stumbo says University of Michigan misled her about the size of the project and voiced concerns about noise, vibration, and possible environmental impacts.