Overview:

-With $4.1 billion allocated for fiscal 2025, the LIHEAP program aids states, territories, and tribal nations.

-Advocates warn that ending LIHEAP could devastate families.

-“Just because the bill gets paid, people should not assume that that's not at great cost,” says Olivia Wein, senior attorney with the National Consumer Law Center.

by JESSICA KUTZ

The 19th

This story was originally reported by Jessica Kutz of The 19th. Meet Jessica and read more of her reporting on gender, politics and policy.

The Trump administration wants to eliminate the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), a little-known piece of the social safety net that helps low-income people pay their utility bills.

Congress created the program in 1981, initially to help people pay for heating in the winter. The program — which has had broad bipartisan support — has increasingly been used to pay for cooling as summers grow hotter and more dangerous to human health due to climate change.

At a recent budget hearing, Sen. Lisa Murkowski, an Alaska Republican, called the program a “lifesaver” for residents in Alaska when questioning Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. about its future.

Kennedy acknowledged the importance of the program but also said Trump’s proposal to eliminate the funding was based on the expectation of lower future energy prices. Yet according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, residential energy prices are expected to go up in much of the country at least through 2026.

Murkowski and lawmakers from across the aisle have been pressuring the administration to commit to funding the program, which provided $4.1 billion to states, territories and tribal nations in fiscal 2025. But the administration has not only called to defund the program in its entirety, but also has put the staff that administer the program at Health and Human Services (HHS) on leave.

Advocates say the end of the program could be disastrous for households who rely on other government benefits that are also under threat, like the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, which are both facing deep cuts.

As the funding of LIHEAP continues to be debated on the national level, here’s an explanation of what the program does and who it helps:

What does the Low Income Housing Energy Assistance Program do?

LIHEAP helps about 6 million households pay their heating- and cooling-related utility bills annually and prevents disconnections through an emergency assistance fund. The payments typically go directly to the utility companies.

States tailor the program to best fit the needs of residents. For example, in places like Arizona, where extreme heat kills hundreds of people a year, a higher allocation of funding goes to cooling assistance. In some states, funds can be used to repair furnaces or air conditioning units.

States are required to account for both a household’s income and its energy burden, or the percentage of a family’s income that goes to pay utility bills, to target those most at risk for utility disconnections.

Low-income households typically have higher energy burdens, often due to homes with poor insulation or drafty windows and doors.

Who does it help?

The LIHEAP program targets households with family members who are particularly vulnerable to extreme temperatures. In fiscal 2023, the program reached 2.1 million households where a resident had a disability; nearly 1 million households that had small children; and 2.4 million households that housed an elderly person.

Both children and the elderly are more sensitive to extreme temperatures because they are physiologically less able to regulate their body temperature. People with complex medical needs also shoulder higher energy costs, due to electricity-dependent medical equipment.

Single parents, who are disproportionately women, are more likely to be energy insecure, as are rural residents, Black, Indigenous and Latinx households.

And the people who utilize the program are usually on the brink of an emergency — either already disconnected from their utility or on the verge of it. “By the time they’re reaching out for help, it’s that their situation has escalated,” said Diana Hernandez, an associate professor and sociologist at Columbia University who studies energy insecurity.

Only about 17 percent of eligible households receive LIHEAP assistance, said Hernandez, who has been pushing to increase funding for the program.

“The money always runs out,” she said.

Mark Wolfe, executive director of the National Energy Assistance Directors Association, an organization that works with state officials to implement LIHEAP, said electricity costs are going up at a higher rate than inflation and that rising temperatures are also leading to a greater need for cooling.

“In Southwestern states the length of the [heat waves are] getting longer,” Wolfe said. “The bills are going up, and a lot of housing is just poorly built … so the costs are going up faster than expected,” he said.

REPORTING FROM PLANET DETROIT

Trump cuts jeopardize energy assistance for over 400,000 Michiganders: ‘Devastating’

The Trump administration’s decision to cut thousands of federal health agency employees, including the entire staff of the Low Income Energy Assistance Program, threatens the future of a vital service that aids over 400,000 Michigan residents with their energy bills.

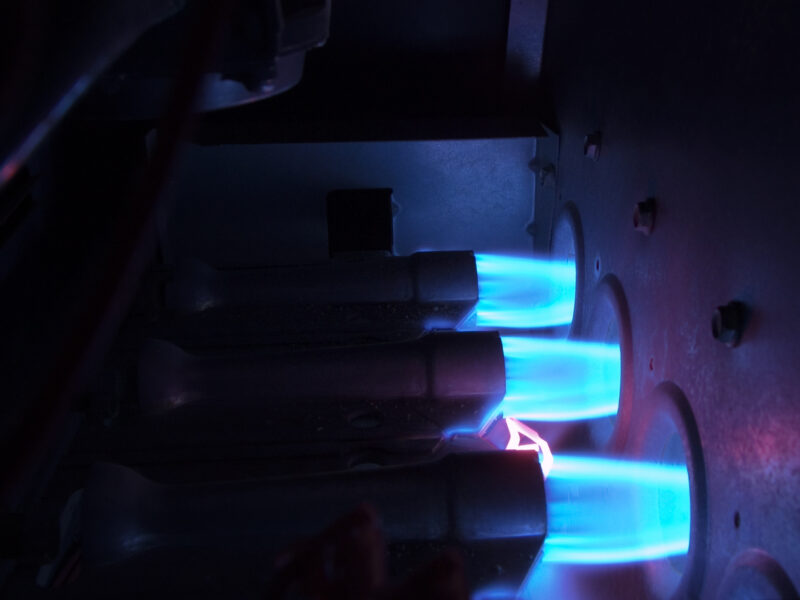

Could Trump make it easier for DTE to build natural gas plants?

DTE CEO said efforts to roll back clean energy rules could facilitate natural gas buildout, provide “flexibility” on coal plant retirements. Experts warn building new gas plants could put ratepayers on the hook for stranded assets.

DTE Energy, Consumers Energy shareholder returns drive up Michigan energy bills: ‘It’s costing consumers so much money’

A national study reveals investor-owned utilities are charging U.S. ratepayers up to $50 billion annually for shareholder profits.

Why is it important?

LIHEAP has multiple benefits that all center on keeping people safe and healthy in their homes, advocates say.

While in many states residents have some protection from a utility disconnecting their electricity, without energy assistance programs like LIHEAP more households would likely keep their homes at dangerous temperatures to keep their bills down.

In a Census Household Pulse Survey from 2024, nearly 23 percent of households reported keeping their homes at unsafe temperatures over the previous 12 months due to rising energy costs.

But doing so is risky in places like Maricopa County, where Phoenix is located. While there is a moratorium on electricity shutoffs during the summer, in 2024, 138 people died indoors of a heat-related cause, with 18 percent of those deaths in a home where the AC was functioning but not turned on. Seventy percent did not have a working AC unit in a place where average summer temperatures are over 100 degrees.

These deaths occurred in a state where over 20,000 households received LIHEAP assistance in fiscal 2023, according to the National Energy Utility Affordability Coalition, which tracks state use of funds.

Without the program, “we’ll be having more and more of these unnecessary deaths,” Wolfe said.

Helping to pay energy bills has also been shown to help keep families more food secure. According to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, 20 percent of U.S. households said they skipped meals and medicines to pay for electricity bills in 2020, a time when households were under additional stress due to the pandemic. And in a 2019 survey of LIHEAP recipients, 36 percent said that before they began to receive energy assistance, they went without food for at least a day to pay utility bills.

It’s called the “heat or eat” phenomenon.

“Just because the bill gets paid, people should not assume that that’s not at great cost,” said Olivia Wein, senior attorney with the National Consumer Law Center. But with multiple social welfare programs facing deep cuts, “it’s going to be harder and harder for people to do that, to juggle enough to get the bills paid on time,” she said.

Wein points out that people’s housing security could also be impacted. Maintaining a utility connection is a condition on many housing leases, and without LIHEAP, more people could face evictions, Wein fears.

She’s also worried children could be taken from their parents. “Not having heat in the winter could result in Child Protective Services getting involved because your home is not habitable,” she said. “So there are all of these ripple effects from unaffordable energy that we will unfortunately see on the grand scale without a strong LIHEAP program.”

Where does the program stand now?

For fiscal 2025, all of the program’s funding has already been released, so residents won’t see an impact until fiscal 2026, which starts in September. But even if the program is funded, Wein says there will be issues with disbursement because of the federal layoffs.

While each state develops individual programs, they still have to run their plans by the federal agency every year to determine state allocations, Wein said. This plan is also accompanied by a complicated formula that happens each time funding is released. Right now only four people are managing the LIHEAP program on the federal level; after the entire office was laid off in April. Wein predicts this will delay funding being sent to the states.

HHS did not respond to a request for comment by press time.

Additionally, community action agencies, places around the country where people go to apply for benefits like LIHEAP, could be shut down, due to a separate move to defund the Community Services Block Grant. This would make it harder for residents to apply to the program. “We need that funding as part of our whole ecosystem,” Wein said.

Trump also sought to zero out LIHEAP funding in his first term, but Congress ultimately is in charge of approving a budget. But Wein said the precarity of the program feels different this time around. “Congress is really looking at cutting, cutting, cutting, cutting. … Things that you would never imagine being cut like entitlement programs are in live discussion right now. So that’s the unknown.”

Advocates say that there really isn’t any other comparable safety net for residents seeking energy assistance if LIHEAP ends up being cut. Though alternatives like charitable giving and religious organizations can help pay for energy costs, it doesn’t come close to meeting the needs of 6 million people who were previously reached by the program, Wein said.

“There is no easy fix and there is no comprehensive fix to losing LIHEAP,” she said. “Every state is going to be devastated with the loss of this funding.”